Policy

the Faces behind the cases

Defining Terms: Framing Women on the Move in Policy Context

The policy element to this campaign serves as background information to contextualise women on the move with data and relevant figures. Each woman is so much more than their legal status. There is differentiation; different legal backgrounds and therefore rights are afforded to migrant and refugee women. The term “migrant” is used to refer to both realities. While “Third country national women” (a term which covers both migrant and refugee women) is used in the Eurodiaconia policy paper, it is felt that impersonal, legal definitions were out of place in this campaign. For that reason, in our campaign text, we use the term “women on the move” and in our policy paper we use the terms migrant and third country national women.

FACING THE FACTS

In Europe today, more than half of the migrant population are women, yet their stories remain at the margins of the public debate. While women made up 47.9% of the world’s migrants in 2020, in Europe they slightly outnumber migrant men, representing 51.6% of 86.7 million migrants.[1] Since February 2022, this gendered reality has become even more pronounced and visible, as most people fleeing the war against Ukraine were women and girls.

Despite their presence and contributions, migrant and refugee women remain one of the most excluded groups when it comes to access to quality employment, vocational training, language support, and social inclusion services. Indeed, they face the so-called “double” or “triple disadvantage”, marginalised due to the intersection of their gender, migration or refugee status, and often other factors such as ethnicity, disability or socio-economic status.

In over two-thirds of EU and OECD countries, employment gaps between migrant women and native-born women are significantly wider than those experienced by migrant men, a reflection of rooted structural inequalities. For refugee women, these are reinforced by forced displacement, trauma, lack of documentation, and caregiving burdens when they arrive accompanied by dependent family members. All of these can restrict migrant and refugee women’s opportunities to meaningfully engage in social inclusion pathways and secure sustainable, decent and fair employment.

AT FACE VALUE

‘the Faces behind the Cases’ aims to bring visibility to these realities. By sharing the lived experiences of Mila, Kati, Aya, Fatima, and Iryna, we invite you to reflect beyond statistics. Each story is a window into their daily hopes and strategies to navigate a new life being a migrant woman in Europe.

These are not exceptional cases. They reflect the broader, and often invisible structural and individual obstacles faced by third-country national women across Europe.

Their experiences highlight the systemic and intersecting barriers that increase migrant and refugee women’s vulnerability to in-work poverty, labour exploitation, racism and social exclusion. At the same time, they expose policymaking gaps: current labour market integration frameworks are too often fragmented, shaped by competitiveness and demographic needs, gender-blind, and disconnected from the realities of those affected by them.

OBSTACLES FACED

1. Language barriers and late access to social inclusion and integration services

Lack of early access to language learning and inclusion services remains a major obstacle to both social and labour market participation. Language learning is not only essential to access employment, but also to support participation in public life, education, and community networks. However, services are often delayed due to administrative conditions or status-related restrictions. When available, they are frequently underfunded, inflexible and disconnected from women’s daily realities (from caregiving responsibilities to employment aspirations). For those in more precarious situations, access is further limited by lack of outreach and entry points.

Recommendations:

- Guarantee early and inclusive access to language and social inclusion services for all, regardless of residence status.

- Integrate part-time work and language learning pathways to enable parallel labour market participation and learning (EU Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027, COM(2020)758).

- Promote and support sector-specific language courses aligned with national qualification frameworks.

- Provide flexible and family-friendly formats supported by childcare options for those attending courses (European Care Strategy, COM(2022)440).

- Invest in community-based outreach to build trust and ensure that information about social services and learning opportunities reaches migrant women.

2. Educational gap and over-qualification

Migrant women are often overrepresented at both ends of the educational spectrum. Compared to native-born women, they are more likely to have either lower levels of formal education, or high-level qualifications that are not recognised.[1] Around 40.7% of migrant women are prone to be overqualified, compared to the 21.1% of EU-born women.[2] This results in lower levels of career satisfaction, limited career progression, and decline in overall well-being.

Recommendation:

- Ensure fast, transparent and affordable recognition of qualifications and prior learning for third country nationals, with targeted support for migrant women to regain access to their professions or having the opportunity to enter new ones. This should include both formal recognition of foreign diplomas and the validation of informal and non-formal learning. This is particularly in sectors where migrant women are overrepresented (EU Skills Agenda, Council Recommendation on the validation of non-formal and informal learning).

- Invest and expand access to on-the-job learning, mentoring schemes and upskilling pathways, ensuring they are adapted to caregiving responsibilities and linguistic diversity. These efforts should actively include migrant women in national and regional skills strategies.

- Uphold principles 1 and 5 of the European Pillar of Social Rights, which affirm everyone’s right to quality and inclusive education and training and to secure employment that matches their skills and aspirations.

3. Legal barriers to residence, employment and access to rights

The administrative status of migrant and refugee women significantly affects their access to employment and social inclusion. Those admitted under family reunification schemes may face legal restrictions on employment for up to a year, reinforcing dependence on spouses and leading to deskilling. For asylum seekers and undocumented women, waiting periods, uncertainty, or lack of clear rights prevent or delay their access to employment. At the same time, limited awareness of social and labour rights, restrictive visa conditions and working permits tied to one employer also limit their bargaining power and increase vulnerability to exploitation

Recommendations:

- Consider regularisation schemes for migrant women already working in Europe and who may be in irregular or precarious employment situations. Such schemes promote access to labour rights, formal employment, and social protection.

- Ease employment restrictions for family reunification cases, ensuring that spouses can access the labour market without delay. For asylum seekers, no later than 6 months (Recast Reception Conditions Directive2024/1346).

- Simplify procedures under the Single Permit Directive (2021/1883/EU) to allow access to employment and residence permits for all skills levels, not just highly qualified workers.

- Strengthen enforcement mechanisms of EU labour directives to ensure that all workers, regardless of their migration status, are adequately protected. This includes enforceable rights to fair working hours, adequate resting periods, and protections against overwork and exploitation, as well as mechanisms to monitor compliance and deter exploitative practices. (Working Time Directive 2003/88/EC, Single Permit Directive 2011/98/EU, Employer Sanctions Directive 2009/52/EC, Victim’s Rights Directive 2012/29/EU)

- Strengthen the capacity and cultural competence of public employment services, including through multilingual information on residence rights, labour protections, and complaints mechanisms.

4. Family obligations and gender roles

Migrant and refugee women often carry the main responsibility for childcare and domestic work, limiting their access to employment, training, and language courses. These unpaid care roles are intensified by the lack of affordable childcare or long-term care for family members, lack of flexible social inclusion programmes, and insufficient work-life balance policies. As a result, many women are excluded from integration opportunities or even pushed to not work or accept part-time or low-paid jobs that can accommodate these responsibilities at the cost of career development. Addressing these barriers requires gender-responsive labour market integration policies that reflect the EU’s commitments to equality, social inclusion and care.

Recommendations:

- Finance accessible and affordable childcare services, especially in remote areas, and integrate care support within social inclusion, employment and training schemes (EU Care Strategy, Barcelona targets).

- Ensure that EU and national Gender Equality Strategies and frameworks (including the upcoming Roadmap for Women’s Rights), explicitly address the realities of migrant and refugee women. This includes recognising unpaid care barriers, residence status and labour market segregation. Intersectionality, as a central pillar of the current Gender Equality Strategy, must be implemented by aligning equality and social inclusion frameworks, particularly, the upcoming EU Anti-Racism Strategy and the EU Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion

Uphold Principle 9 of the EPSR affirms the right to work-life balance and to address gendered obstacles to labour and social participation. These efforts must go in line with Principle 2 on gender equality and Principle 3 on equal opportunities, regardless of migration status.

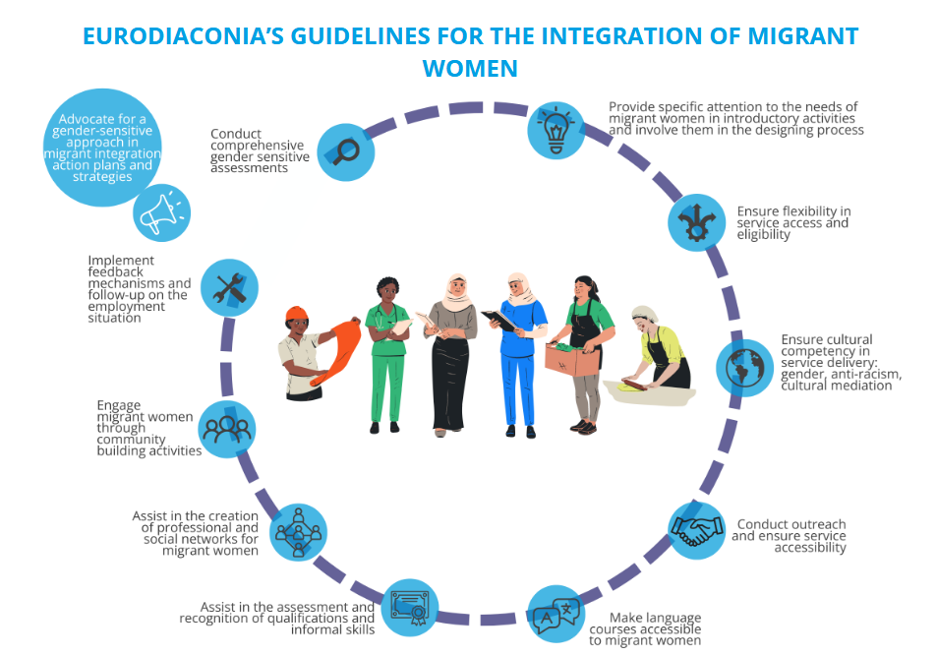

From Principles to Practice: Guidelines for Inclusive Integration

Structural reforms must go hand in hand with the way social services are delivered. Based on the experience of Eurodiaconia members, these are some of the concrete practices that should guide integration support to make it more inclusive, accessible and grounded in the everyday realities of migrant women:

- Services need to take into account caregiving responsibilities, trauma, and specific vulnerabilities which may affect migrant women ability to access integration services, training or employment. /8-9/

- Language learning must be accessible and flexible, with part-time and profession focused options, ideally supported by childcare. /10-11/

- Integration services should be open to all, regardless of their status to not exclude women in precarious situations. /9/

- Labour market integration services should help identify and build on informal skills when designing personalised support and mentoring /9/

- Staff working in employment and integration services should be trained in anti-racism, gender equality and intercultural sensitivity. /12/

- Migrant women should also be directly involved in shaping the services that affect them, through co-design, peer support and regular feedback systems. /13-14/

- Community-based approaches are essential to build trust, accountability and long-term engagement. /13-14/